At a Glance

- Mrima Hill in Kenya is estimated to hold over $62 billion worth of rare earth minerals, including niobium used in electric vehicles and renewable energy systems.

- U.S., China, and Australia are showing growing interest in the site as part of their efforts to secure global supply chains for critical minerals.

- Local Digo communities fear displacement and cultural loss, as Kenya seeks to balance foreign investment with environmental and social protection.

Kenya is quietly emerging as a new flashpoint in the global race for critical minerals as the United States, China, and others turn their attention to the country’s southern coast.

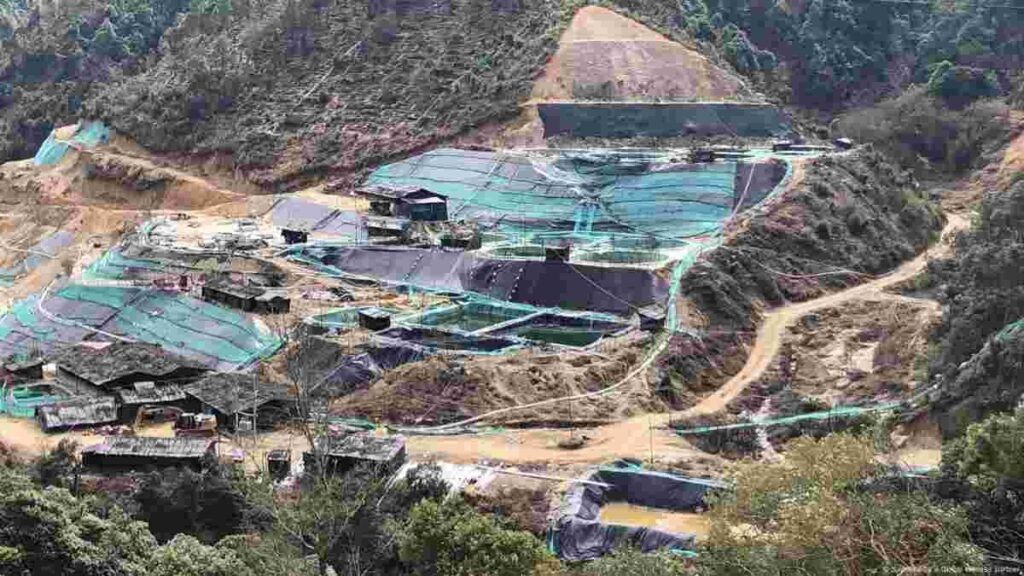

On the forested slopes of Mrima Hill in Kwale County—land long revered by local communities—an international contest is unfolding over resources vital to the clean energy transition.

Stretching across about 157 hectares, Mrima Hill is believed to contain one of Africa’s richest deposits of rare earth elements, including niobium, a metal used in electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and advanced electronics.

Early studies by Cortec Mining Kenya, a subsidiary of UK- and Canada-based Pacific Wildcat Resources, estimate the site’s mineral wealth at more than $62 billion.

As global powers race to secure mineral supply chains, Kenya’s little-known site has attracted renewed attention from investors, diplomats, and rival governments.

Washington and Beijing—each eager to strengthen control over clean-tech manufacturing—are increasingly viewing Africa’s mineral wealth as the next frontier of economic influence.

For Kenya, this new spotlight brings both promise and pressure: the potential for investment and jobs, but also fears of cultural loss and environmental damage.

Rival interests on sacred ground

In June, then–U.S. ambassador to Kenya Marc Dillard visited Mrima Hill, signaling Washington’s growing interest in diversifying supply chains away from China.

His visit followed months of outreach under the U.S. Minerals Security Partnership, a program meant to secure access to key resources from trusted partners.

China, which dominates the global rare earths market, has also shown renewed attention.

The South China Morning Post reported that several Chinese nationals recently attempted to enter the Mrima Hill area but were turned away by local guards—an episode that highlighted the site’s geopolitical sensitivity.

Australia is joining the race, too. RareX and Iluka Resources, both based in Perth, have expressed interest in exploring Mrima Hill.

Local reports suggest speculators are already buying land around Kwale’s coastal villages in anticipation of future projects.

Local concerns amid mining ambitions

For the Digo community, which inhabits the area, the renewed global interest comes with unease.

Mrima Hill is considered sacred, home to ancestral shrines, medicinal plants, and ancient graves.

Many residents depend on its slopes for farming and forest resources, with more than half living below the poverty line.

“People come here with big cars, but we turn them away,” said Juma Koja, a local forest guard, in an interview with Agence France-Presse.

“I do not want my people to be exploited again.”

Others see opportunity. “Why should we die poor while we have minerals?” asked Domitilla Mueni, a farmer who hopes future projects could bring development to the region.

Kenya’s mining crossroads

Kenya’s mining sector has long been held back by disputes among investors, regulators, and politicians.

In 2013, authorities revoked Cortec Mining’s license to operate at Mrima Hill, citing environmental violations and irregular licensing.

The company accused then–Mining Minister Najib Balala of corruption, which he denied.

To restore investor confidence, Nairobi later imposed a moratorium on new mining licenses, lifted only recently after introducing reforms such as digital licensing, tax incentives, and transparency measures.

The government aims to raise mining’s contribution from 0.8 percent to 10 percent of GDP by 2030.

Africa’s role in the global minerals race

Across Africa, governments are rethinking how to manage mineral wealth as competition between China and the West intensifies—from Zambia’s copper to Namibia’s lithium and Congo’s cobalt.

The African Union’s Green Minerals Strategy now encourages nations to move beyond raw exports toward refining and manufacturing within the continent.

“There’s a romantic view that mining is an easy way to get rich,” said Daniel Weru Ichang’i, a retired geologist from the University of Nairobi.

“But without strong institutions and clear oversight, it can easily go wrong.”

For Kenya, the challenge is clear: to protect the heritage of Mrima Hill while ensuring any mining benefits local communities.

The world may see a $62 billion resource, but for those living under its canopy, it remains something more enduring—home.